We have seen that Copernicus overthrew the Ptolemaic theory of the universe by proving it to be heliocentric rather than geocentric (see Lecture 6). But Copernicus kept the old astronomy by retaining the system of spheres and epicycles. Copernicus had little understanding of the plurality of worlds or universes or of the free motion of the heavenly bodies in space. It remained for the Italian philosopher, GIORDANO BRUNO (1548-1600), to make the first complete assault on Ptolemaic astronomy and the philosophical assumptions associated with it.

Click here for more about BrunoBruno was born at Nola, near Naples, in southern Italy. At an early age he entered the Dominican order in Naples. Charged with heresy in 1576, Bruno fled the convent and the Dominicans and traveled widely across Europe. His spirit was in rebellion against the more reactionary aspects of Catholicism, while his Catholic antecedents made many Protestants suspicious of him. Therefore, Bruno was not entirely welcome in either camp. This is especially important to recognize since his short life spans the period in which Catholics and Protestants were engaged in heated battle.

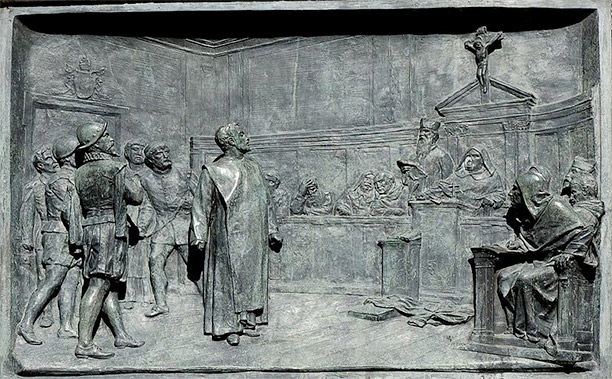

However, Bruno was honored by scholars and he taught at many important centers of learning, among them Toulouse, Paris, Oxford and Wittenberg. He made the mistake of returning to Italy (1591), was betrayed by one of his pupils in Venice, and turned over to the Inquisition. At the end of the Venetian trial he recanted his heresies, but was sent to Rome for another trial. Here he remained in prison for eight years, at the end of which he was sentenced as a heretic and, in February 1600, was burned alive on the Campo de’ Fiori, the first conspicuous martyr to the new world view.

Bruno mastered the existing body of mathematics and understood the Copernican system. Although he had at his disposal the necessary preparation for carrying out his an astrophysical revolution, it was conceived within a devout and pious mental climate. In the old astronomy, the earth was regarded as the center of the universe. Copernicus had replaced the earth with the sun as the center of the system. Bruno argued that there can be no such limitation of the physical universe as was implied in the system of crystalline spheres. There is neither limit nor center to the universe. Everything depends on the place of observation. Each observer on the earth may regard his point of observation as the center, but it would no so appear to an observer on the sun or on one of the other planets or the fixed stars.

Everything, then, is relative to the point of observation. Position is relative. Up and down are terms that have precise meaning only when used in regard to a particular spot in the universe. The same applies to motion — it is likewise relative. There is no absolute direction. Time is also relative.

Bruno’s notion of relativity not only upset the old astronomical conceptions, it also challenged a basic notion in Aristotle’s physics. Aristotle (384-322) had suggested that light and heavy are absolute phenomena. Heavy matter seeks the center of the universe. This is the earth, and the earth is the heaviest element. Bruno insisted that this is an error as it assigns false importance to the earth.

Even more revolutionary was Bruno’s hypothesis of a plurality of worlds and universes. Not only may there be other earths like ours — other universes may exist as well. Further, Bruno repudiated the notion that the materials in the heavens are of a higher order than earth, air, fire and water. And it had been assumed that the heavenly bodies are composed of a mysterious fifth element, the “aether.” Bruno believed that other heavenly bodies are presumably made up of the same materials as the earth, a guess which required the spectroscope of the 19th century to prove scientifically valid.

Finally, Bruno broke away from the notion of fixed starry spheres and epicycles. The heavenly bodies move freely in space, he declared, although it required the work of Galileo (1564-1642), Kepler (1571-1630), and Isaac Newton (see Lecture 7) to elucidate the problems associated with their movements and orbits. These ideas Bruno illustrated in three works: On Cause,Principle and Unity; On the Infinite Universe and the Worlds; and On the Immeasurable and Countless Worlds.

Since the medieval world view had revolved about the Christianized Ptolemaic system, embodied in Dante’s Divine Comedy, it is not difficult to see why the faithful might have looked upon Bruno with horror. He challenged geocentrism, refuted the dogma of the perfection of the heavens, and suggested that there might be a vast number of other worlds as well as universes. This last idea was particularly disconcerting. Though Bruno had no such purpose in mind, it directly opposed the creation tale specified in Genesis and constituted a grave challenge to the divinity of Jesus. Bruno’s heresy in the eyes of the Church is perhaps understandable, particularly when he put it in clear and popular language. There was a very real danger that Bruno would stir up widespread skepticism of the Christian world view. Yet Bruno himself was not an agnostic nor did he embrace a mechanistic outlook. He regarded God as at work in a creative and directive capacity in every part of the vast universe of universes which he imagined. In his theology and in his views of God and Nature, Bruno was a pious mystic and ardent Christian.

The engine behind the drive for hospital reform in the mid-nineteenth century was Florence Nightingale (photo, left). After her tremendously successful humanitarian venture at the Scutari Barrack Hospital during the Crimean War, Nightingale was able to convince the world of the necessity of improving hygiene and sanitation as well as having trained professional nurses tending the sick in the hospital wards. According to medical historian Guy Williams, when she arrived at Scutari “there were plenty of rats, lice and fleas, but there were very few knives, forks, or spoons. Miss Nightingale and her nurses, who were allowed just one pint of water per person per day for washing and drinking and for making tea, [yet]…the ladies’ own personal circumstances were hardly hygienic.”(4) With hard work and determination, she turned the situation around and by the time she returned to England, she had become a national heroine.

The engine behind the drive for hospital reform in the mid-nineteenth century was Florence Nightingale (photo, left). After her tremendously successful humanitarian venture at the Scutari Barrack Hospital during the Crimean War, Nightingale was able to convince the world of the necessity of improving hygiene and sanitation as well as having trained professional nurses tending the sick in the hospital wards. According to medical historian Guy Williams, when she arrived at Scutari “there were plenty of rats, lice and fleas, but there were very few knives, forks, or spoons. Miss Nightingale and her nurses, who were allowed just one pint of water per person per day for washing and drinking and for making tea, [yet]…the ladies’ own personal circumstances were hardly hygienic.”(4) With hard work and determination, she turned the situation around and by the time she returned to England, she had become a national heroine.